“Who do we want to be with

when we die?” That was the question. Should we be with each other or with our

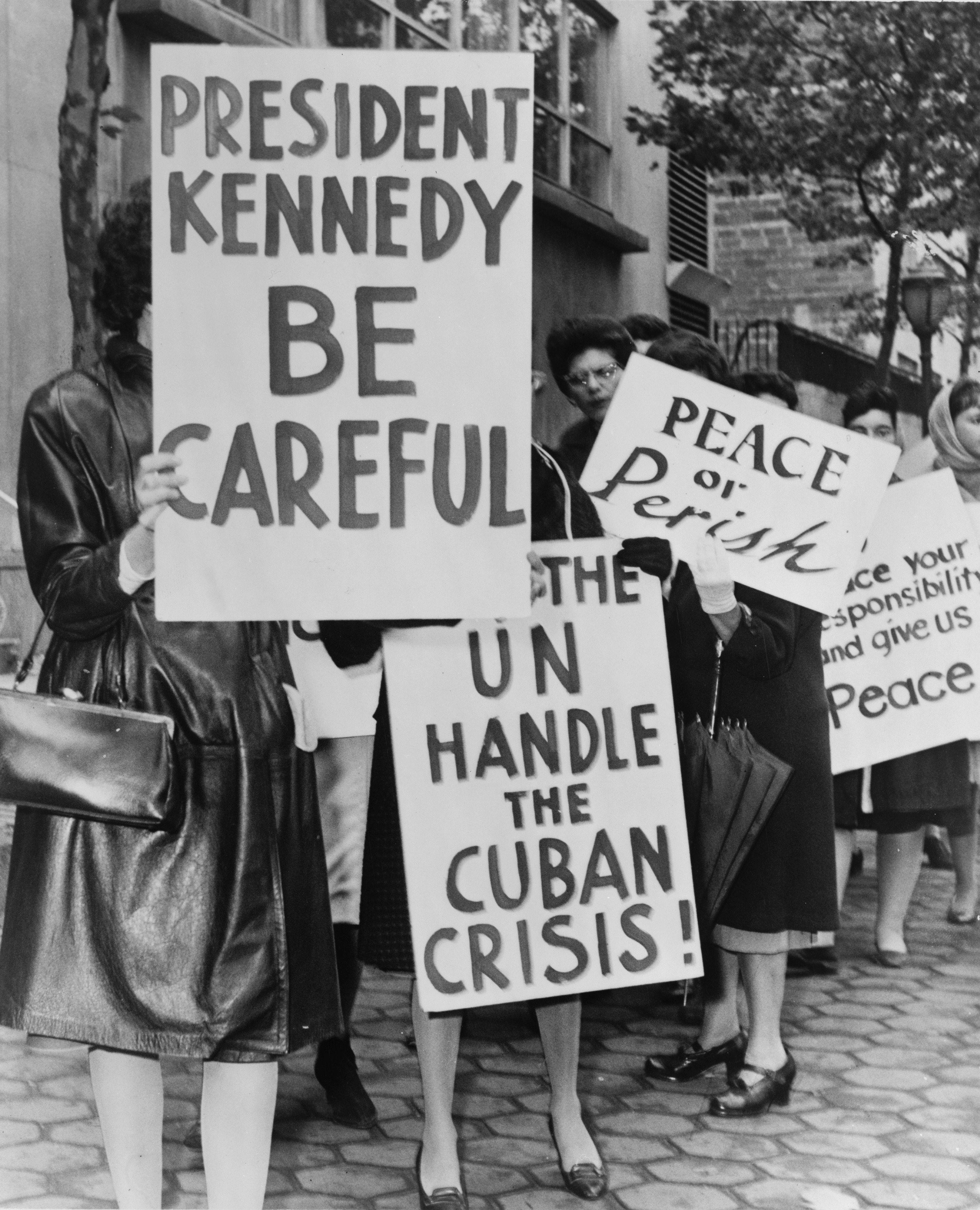

families? I was a senior in high school during the Cuban missile crisis, and

that was the question we asked each other as we heard about the Soviet missiles

in Cuba and about “our” response.

“Who do we want to be with

when we die?” That was the question. Should we be with each other or with our

families? I was a senior in high school during the Cuban missile crisis, and

that was the question we asked each other as we heard about the Soviet missiles

in Cuba and about “our” response.

I don’t remember being

shocked that we were asking that question. We were accustomed to the idea of “mutually

assured destruction.” We all knew that if someone — i.e., the Soviets or us —

launched a nuclear missile, the other side would

launch its missiles. Mutually assured destruction — and I don’t know of anyone

who commented, then, on the acronym. It was the official policy of the nuclear

age, the way to keep us safe — Mutually Assured Destruction, MAD. It was

madness we had come to accept, and that acceptance was another kind of madness.

One of the unexpected joys

about sitting in a doctor’s waiting room is finding old magazines, sometimes

with really interesting articles. That’s how I found “John F. Kennedy's Vision

of Peace” by Robert Kennedy, Jr, in Rolling Stone.

The article explores Kennedy’s

efforts to create peace and some of the challenges he faced. It recounts some

of the insane ways that people were willing to risk a nuclear war if we could

obliterate the Soviet Union.

Kennedy comes out the hero of

this article, perhaps not surprisingly, but it does seem clear that his

commitment to find a way to peace was pivotal. As disturbing as the attempts

were to goad us into nuclear war, it is equally disturbing to see that we

avoided that war only with the help of a lot of luck.

The Cuban missile crisis was

more than 50 years ago, but it is the closest — that we know of — to the world

experiencing mutually assured destruction. Though we — the US and the Russians —

no longer espouse mutually assured destruction, we still have more than enough

nuclear arms to destroy the earth many times over. And these missiles — some in

silos, some aboard submarines — are still targeted at Russia and at the United

States.

There are several obvious but

often forgotten lessons to be taken from the Cuban missile crisis.

- We have to talk to the enemy. Without talk, there will be no peaceful resolution. If we do not talk to the enemy, we will rely more and more on our bomb-throwers and the enemy is more likely to rely on his bomb-throwers.

- The enemy has reasons and motives that are felt as strongly as we feel ours. And we must allow that the reasons for the actions we loathe may be quite reasonable to him. Even as we despise what the enemy is doing, even as we are goaded into hatred, we must allow that the enemy is behaving for many of the same reasons we are behaving.

- Negotiations are a way of seeking a settlement that is useful to all of the parties. If it is not useful to everyone, it will not be maintained. But useful does not mean that everyone gets their way. If everyone could have had their way originally, there would have been no conflict. But everyone may have increased security, for instance, or increased independence.

And unfortunately it’s not

over, even when we think it’s over. The potential for nuclear accident and

nuclear stupidity are still with us. The odds of something happening are

greatly diminished, but it’s not over.

And that’s a final lesson. As

each crisis fades from our attention, as the media moves on to the next new or

potential or invented crisis, there is much still to be done if we are to

create a peaceful world, not a world that lurches drunkenly from one adrenaline rush to the next. As we lurch drunkenly into the next

crisis, hysterical screaming for justice or human rights or advancing the

American presence, we must remember these lessons. We must talk with Syria,

North Korea, and Iran, even as we have learned to talk to Russia and China. When we run into difficulties, we need to keep talking.

There will be casualties when

we talk, yes, but put those casualties against the casualties of our

bomb-throwing. Consider the Cuban missile crisis. What would the casualties

have been if we had stopped talking and started tossing bombs?

The final thought: the

pattern of conflict and negotiation, the ways of avoiding bomb-throwing and

finding peace are not confined to international conflicts. These same patterns

of anger, frustration, fear, and violence are present anywhere that people

gather. They apply to the fellow down the street throwing trash into people’s

yards, and they apply to the kids irritating the neighbor by shooting off

fireworks.

We have to learn to talk and

negotiate, even when we don’t want to, if we are to avoid throwing bombs at

each other.

No comments:

Post a Comment