By Emily Wirtz

When Dr. C.T. Vivian arrived on Ashland’s campus Monday, January 19, I was both inwardly and outwardly ecstatic simply to witness from a distance this civil rights legend. It’s not very often that one has the opportunity to meet someone from the history books. At first impression, prior to the event, I’d expected an ordeal—some kind of showy, Obama-esque, “look at my battle scars” kind of encounter. What I got on Monday evening was my grandpa. Granted, there was a glaring difference in skin tone between my biological grandfather and this legend standing before me, but all the same, Vivian was much less and yet so much more than I was expecting.

Down-to-earth and socially-aware are not two descriptions I would usually put together. I see the “check your privilege” bloggers who in the most basic sense are holding themselves on a privileged pedestal with an “I’m better than you because I’m socially aware” aura. Then I see the sincere, stay-out-of-the-way people sitting in the back corner of events like these, not because they’re okay with social injustice, but simply because they’re not public orators. Vivian, in a sense, held the best qualities of both—though obviously he was a public speaker. That is why my impression was that he was my grandfather reincarnate. I know that sounds a bit bizarre. In middle school, I did a history fair project on the March of Bataan in WWII, in which my grandpa was a prisoner of war. When I interviewed him about his experiences, an entirely different person I had no idea was there came through. In that moment, my down-to-earth grandpa became a victim, a hero, and a survivor, doing so with the humility with which I was familiar, but with an additional distance—he was a man from my history books. This is what Vivian became. He began as a legend, someone who existed in textbooks and documentaries but who I’d never encounter in a real-life setting. The privilege of meeting him completely shifted that outlook.

The Ashland Center for Nonviolence began as an ad hoc group of individuals who wanted to challenge the willingness of American society to resort to violence. The ACN instead poses the question, "What else can we do?"

Wednesday, January 28, 2015

Friday, January 23, 2015

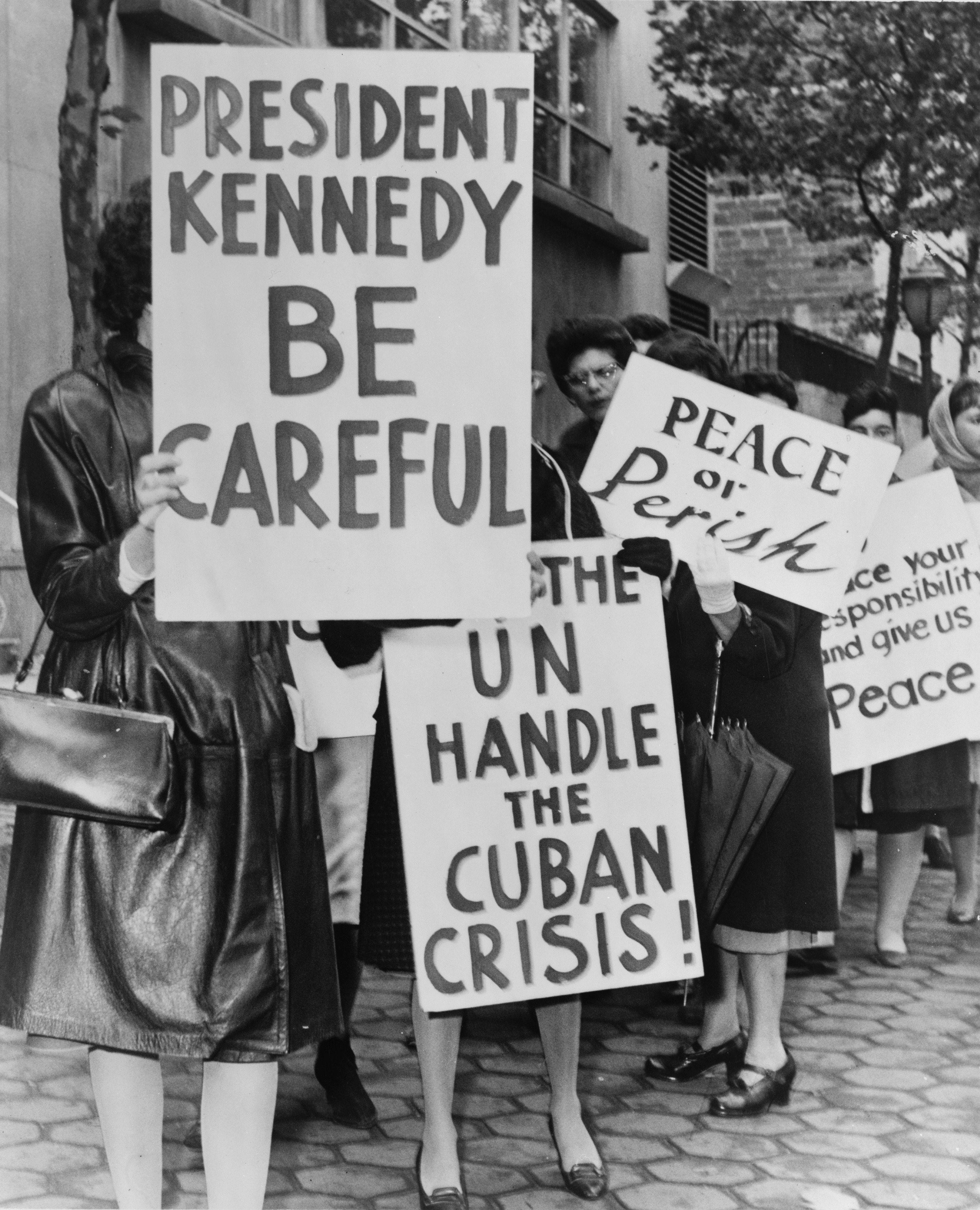

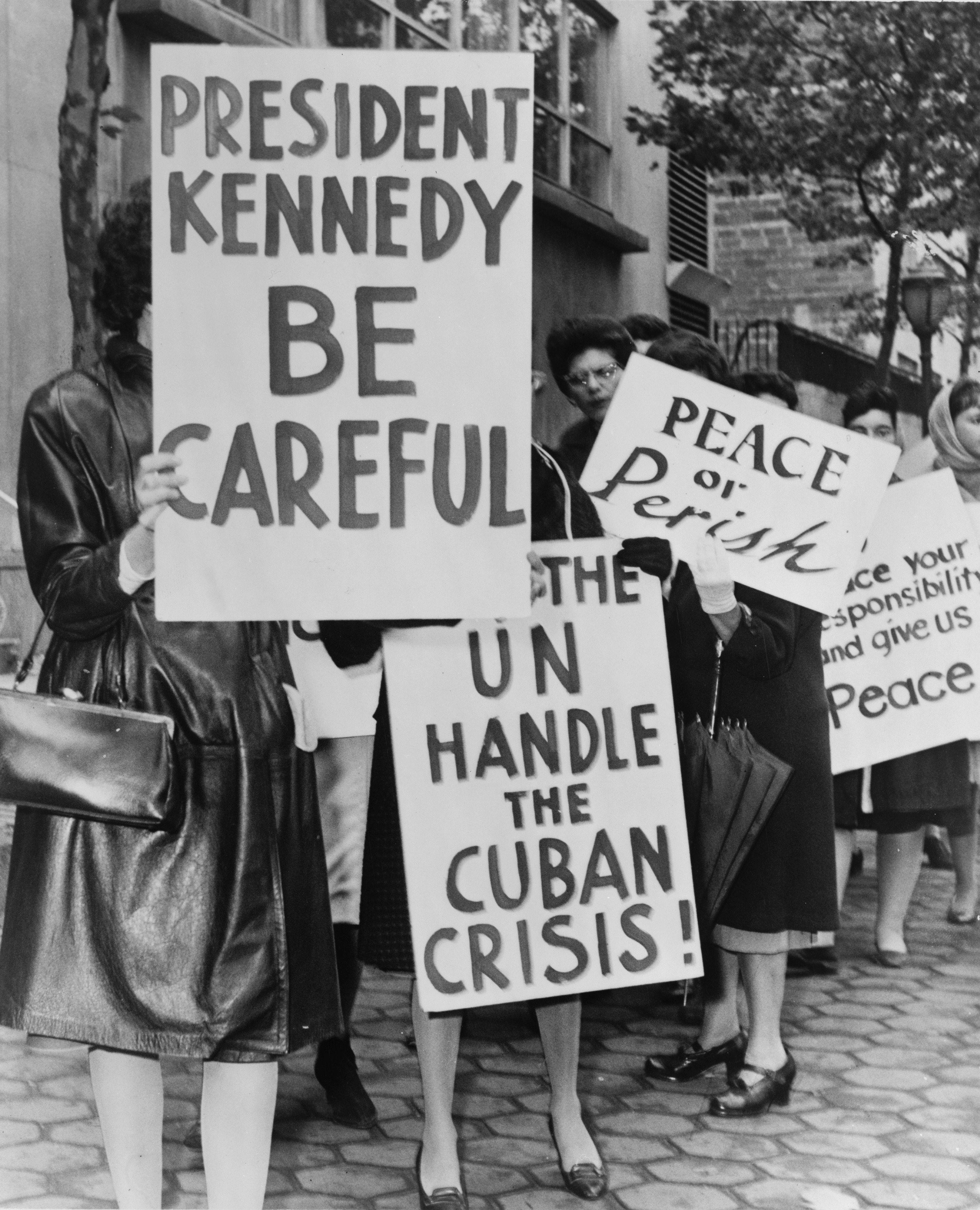

Thoughts on the Cuban Missile Crisis

By John Stratton

“Who do we want to be with

when we die?” That was the question. Should we be with each other or with our

families? I was a senior in high school during the Cuban missile crisis, and

that was the question we asked each other as we heard about the Soviet missiles

in Cuba and about “our” response.

“Who do we want to be with

when we die?” That was the question. Should we be with each other or with our

families? I was a senior in high school during the Cuban missile crisis, and

that was the question we asked each other as we heard about the Soviet missiles

in Cuba and about “our” response.

“Who do we want to be with

when we die?” That was the question. Should we be with each other or with our

families? I was a senior in high school during the Cuban missile crisis, and

that was the question we asked each other as we heard about the Soviet missiles

in Cuba and about “our” response.

“Who do we want to be with

when we die?” That was the question. Should we be with each other or with our

families? I was a senior in high school during the Cuban missile crisis, and

that was the question we asked each other as we heard about the Soviet missiles

in Cuba and about “our” response.

I don’t remember being

shocked that we were asking that question. We were accustomed to the idea of “mutually

assured destruction.” We all knew that if someone — i.e., the Soviets or us —

launched a nuclear missile, the other side would

launch its missiles. Mutually assured destruction — and I don’t know of anyone

who commented, then, on the acronym. It was the official policy of the nuclear

age, the way to keep us safe — Mutually Assured Destruction, MAD. It was

madness we had come to accept, and that acceptance was another kind of madness.

One of the unexpected joys

about sitting in a doctor’s waiting room is finding old magazines, sometimes

with really interesting articles. That’s how I found “John F. Kennedy's Vision

of Peace” by Robert Kennedy, Jr, in Rolling Stone.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)